Raising Hell: The Book Issue: "We're Not Going to Apologise"

"For readers interested in how the system hinders change, [Slick] is a timely book." - Books+Publishing, 11 June 2024

Close readers of Raising Hell will notice that things look a bit different this fortnight. That’s because my book, Slick, hits bookstores from today. This is the story of how fossil fuel companies learnt to wield influence in Australia and how they used this power to deny and delay action on climate change. Here’s an excerpt to give you a taste for what’s inside. Pick up a copy from your local bookstore and support independent journalism.

It was somewhere thousands of feet above Los Angeles, his plane helplessly circling above the sprawling metropolis, that Liberal Tasmanian senator Denham Henty first had the idea to investigate the issue of air pollution. He had been in the US, on a tour through Fort Worth and Cape Kennedy, and was making his return when it happened. As the aircraft approached, word came that the smog collecting above the city was too thick for them to land.

When he finally put two feet on the ground, Henty was appalled at what he saw. Caltech scientist Arie Haagen-Smit had made the first connection between the two million cars on the city’s roads and all that smog that hung in the air in 1948. The petroleum industry fought him over the claim, denying there was any relationship at all, but Haagen-Smit’s work was persuasive enough that it started to mobilise action. Still, actually passing the regulations needed to control the problem took time. Even as late as 1958, people wept on LA’s streets due to eye irritations, and some resorted to gasmasks to move about outside.

‘Don’t let this sort of thing happen in your own place,’ people told Henty. ‘Don’t let it happen in your own country.’

Steaming back home, Henty wanted to address the issue before it became a problem in Australia. He decided to muster the collective resources of the senate by creating a committee system that put senators to work investigating practical problems. The first would be the select committees on air pollution and water pollution. George Howard Branson, Liberal senator from Western Australia, would be chosen to head up the eight-person Air Pollution committee. Over the course of 1968 and 1969, the members toured industrial sites and took evidence from experts at companies like

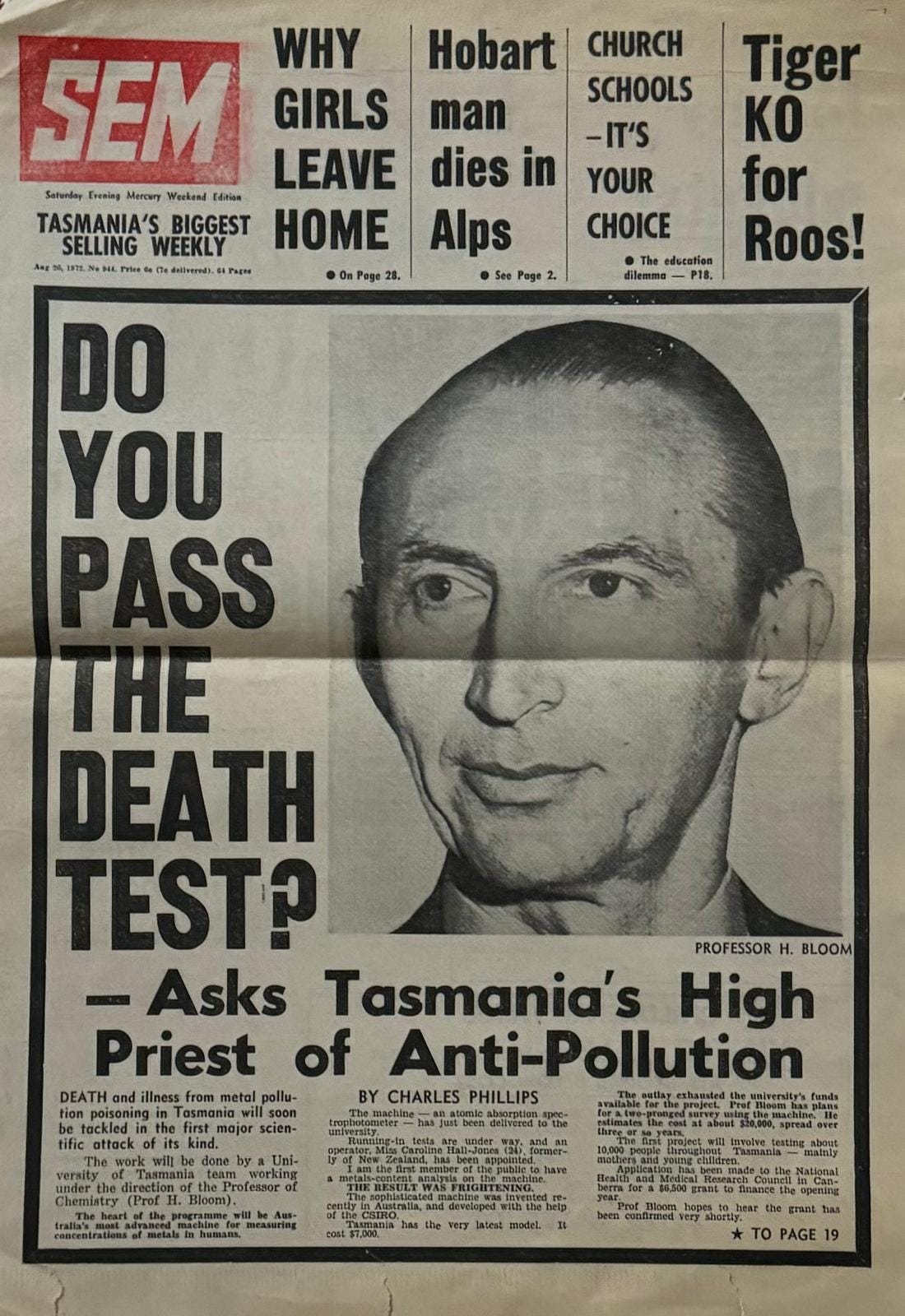

General Motors Holden, Shell, Amoco, Esso, BHP, Alcoa and the corporate predecessor to Rio Tinto. It was on 6 February 1969, at a hearing in Hobart, that they received a startling warning from University of Tasmania professor Harry Bloom. Under the watchful gaze of the committee, Bloom began his address with a declaration: the threat posed by air pollution generation was ‘much more serious than is normally accepted’, and especially so the risk posed by carbon dioxide. He was particularly concerned that no-one seemed to be paying attention to ‘one very important oxidation product of carbon, and that is carbon dioxide’.

He told the committee: ‘Carbon dioxide build-up in the world has been calculated to be such as to be able to produce serious changes, not only in climatic conditions but also in health conditions all over the world in not too many years, say fifty to a hundred years. I think the whole situation is one which needs very desperate and immediate action. I think we have to know what is at present in the atmosphere, and one ought to do something about it.’

The problem was well documented, Bloom later explained, as he had ‘seen some very highly scientific studies of this matter’. Unfortunately, he never named the studies he was referring to in his evidence – a frustrating omission, like so many others in the official record of early discussions of climate change, making it difficult to gauge now exactly what was known when. But there is no doubt that Bloom found what he had read convincing. During questioning, the professor was asked to identify which pollution problem he thought was of most importance, giving him the opportunity to drive his point home:

‘If there is a serious and permanent change of climatic conditions in a state or country, or in the world,’ he said, ‘it could conceivably be impossible to do something about it. If carbon dioxide built up to such an extent in the earth’s atmosphere as to trap radiation from the sun and cause climatic conditions to change all over the world, perhaps heating the whole world and melting the ice caps, nothing could be done about it at that stage. At this stage, when we recognise the problem exists, we ought to do something about it before it becomes too late.’

The minutes of the exchange don’t record the passion with which Bloom delivered these words, but if he thought he would not be believed, Branson was quick to reassure him.

‘You are among friends,’ Branson said. ‘That is why we are here.

The Commonwealth thought this, too.’

Democratic Labor Party senator John Little suggested then that the good professor might be overreacting. ‘As a layman,’ Little said, it seemed to him ‘a rather extreme assumption’ that continuing to add carbon dioxide to the atmosphere might result in catastrophic climate change. There had to be some sort of ‘compensatory factor’, the senator insisted. For example, he said, a hotter planet would generate heat, leading to more evaporation and more rainfall, which might cancel out the warming effect on the poles.

Little was right in a sense: higher humidity on a warmer planet would lead to higher evaporation rates and more torrential rain. But his suggestion that more rain would cancel out the risk of melting ice at the poles was crackpot stuff.

With a nudge from Branson, Bloom answered this ‘gotcha’, explaining that it was nonsense. Though the professor said he was no pessimist – when it came to predictions about cities being swamped by rising sea levels, he did not ‘swallow all of the stories in their grimmest detail’ – he was adamant that he was correct.

‘There have been analyses of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere over a couple of hundred years,’ he said. ‘No doubt exists that carbon dioxide contents in the atmosphere are increasing. There is no doubt that all the processes that cause this increase are escalating rapidly. There is also no doubt whatsoever that the constitution of the atmosphere has a vast influence on the amount of sunlight trapped in the earth’s atmosphere and there communicated to the earth, to the ice caps and so on.’

It wouldn’t take much, Bloom said, to push the ice caps over the edge – ‘only a few degrees centigrade’.

Bloom was a man cursed with unique foresight. He would later carry out the first tests showing the Derwent River was contaminated by heavy metals, prompting an intense backlash from industries that used the river like an open sewer – just as Senator Little had dismissed his concerns about air pollution. But some of the committee members, at least, seemed to have understood.

When Branson went on to table his committee’s final report in September 1969, it would deliver one of the clearest, most direct warnings about the risk posed by the greenhouse effect in Australia at that time. In a section titled ‘Nature of Air Pollution’, the committee reported that ‘air pollution is basically caused by man’s insatiable demand for energy’ and that ‘since man first began lighting fires for warmth and cooking, he has been contaminating to a height of from 30,000 to 50,000 feet the relatively thin layer of air which surrounds our globe’.

It continued:

The burning of coal, oil and natural gas over the years has increased the global concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and although this increase has had no recorded effect on living organisms, it has been suggested by leading scientists that further increases could modify the heat balance of the atmosphere. This could result in marked changes in world climate and ultimately a warming of the earth to such an extent that the arctic ice caps would melt and sea levels would rise by some 400 feet. Many major cities would become inundated as a consequence. A further possibility was that an overabundance of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere could upset the carbon/oxygen balance and interfere with the normal process of plant photosynthesis, which could result in our world exhausting its supply of oxygen. The process of contamination increased sharply as the energy requirements of mankind increased with the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century and again following the general industrial expansion since World War II. Air pollution then can be described as one of the penalties of urban development and technological progress. Man has been using the atmosphere as a huge rubbish dump into which is being poured millions of tons of waste products each year. In the United States of America alone it is estimated that 142 million tons of air pollutants were admitted into the air in 1966, that is almost 400,000 tons each day.

Evidence received by the Committee indicates that an air pollution problem already exists in some parts of Australia and while not yet a problem of the magnitude existing in well known centres of pollution such as London, New York, Los Angeles and Tokyo, a problem which nevertheless warrants urgent planning and action.

Though phrased in terms of probability and not certainty, the frank declaration that ‘man has been using the atmosphere as a huge rubbish dump’ was stunning. Both Branson and the committee’s deputy chair, Condor Laucke, were Liberals; four decades later, foot soldiers within their own party would harangue climate scientists for daring to say as much, blaming sunspots and volcanoes for fluctuations in global average temperature series and doing everything they could to kill off efforts to address the issue through the United Nations.

The report did not investigate the implications of the greenhouse effect any further, but, as a public document, it was available to anyone who wanted a copy. Though its impact would be overshadowed by interest in the Water Pollution committee’s later work, its comments on carbon dioxide were debated in parliament, two of the first books on air pollution would refer to it, and the report’s findings caught the attention of Australian heavy industry.

In 1971, the Australian Minerals Industry Council (AMIC), a forerunner to the Minerals Council of Australia, organised a seminar on environmental issues. Among the invitees was Kenneth Nelson, a scientist from the American Smelting and Refining Company. Unlike Bloom, Nelson was a scientist who always made sure to tell his bosses what they wanted to hear. As vice president for environmental affairs, he had once sought to surreptitiously undermine scientific research linking cancer among smelter workers to exposure to arsenic and sulphur dioxide – a scandal that would only break in 2007. Because Nelson knew those responsible for reviewing the research, he employed a strategy pioneered by schoolyard bullies. Using trusted colleagues to launder his views, he had them badmouth the research to the reviewers, who in turn passed these criticisms on to the authors. The study’s authors, none the wiser, dutifully watered down their conclusions.

On the ground in Australia, Nelson delivered a presentation to the broader resources sector on clean air, in which he went so far as to put solid figures to the problem.

‘Carbon dioxide is really the only contaminant which we can say is proved to be accumulating in the global atmosphere,’ he said. ‘Apparently it is being generated somewhat faster than it can be removed. The atmospheric CO2 concentration is currently about 330 parts per million – up from a bit under 300 parts per million fifty years ago. No cause for alarm, but worth watching on a global scale.’

Not only had Nelson undermined any sense of urgency his audience of anxious resource executives might have been feeling, he had also framed the situation in a way that implied significant doubt. Humanity was responsible for only 2 per cent of the carbon dioxide on the earth, he went on. Despite ‘frequent press reports’ that an increasing CO2 concentration might create a greenhouse effect, he noted that other theories suggested the impact might be offset.

One hypothesis was that particulate in the earth’s atmosphere might increase the planet’s reflectivity – its ‘albedo’ – so that less sunlight made it through to keep the earth warm – though Nelson freely admitted there was no evidence to support this idea. He concluded this part of his presentation by declaring, ‘Natural processes appear to maintain a mysterious balance.’

Humanity had observed the microbe, split the atom and landed on the moon. The suggestion that nature was an enigma, impossible to fully know, was interesting, coming from an alleged man of science. If it was any indication of the seriousness with which Nelson took his work, or the culture he operated within, it was perhaps telling that he closed with a sex joke:

‘In any case, I think we need to worry far more about our libido than our albedo.’

Publications

‘What the gas giants knew all along’ (online, The Saturday Paper, 8 June).

‘Pipeline to power’ (online, The Monthly, 8 June).

Events

Now the book’s live, there will be events — I hear you love events, so I got ‘em in droves. Below are a list of those which are confirmed. Check the website as I’ll be putting up the details of new events as they’re locked in.

Byron Writers Festival: Coffee and Papers

What: Royce Kurmelovs will host Clive Hamilton, Marina Kamenev, Isabelle Reineke to pull apart the week’s news.

When: 8:45am to 9:45am (AEST), Saturday, 10 August 2024

Where: A&I Hall, Bangalow

Tickets: https://events.humanitix.com/byron-writers-festival-passes-2024/ticketsDeadlock: Ending Fossil Fuels

What: Climate scientist Joëlle Gergis (Highway to Hell) and investigative journalist Royce Kurmelovs (Slick) analyse the government paralysis around ending fossil fuels and provide a roadmap for taking action. With Julianne Schultz.

When: 9am to 10am, Sunday (AEST), 10 August 2024,

Where: A&I Hall, Bangalow

Tickets: https://events.humanitix.com/byron-writers-festival-passes-2024/ticketsLAUNCH: Slick: Australia’s Toxic Relationship with Big Oil

What: Join Royce Kurmelovs for the launch of Slick with Isabelle Reinecke

When: 8am to 9:45am (AEST), Saturday, 10 August,

Where: A&I Hall, Bangalow

Tickets: FreeFREE: State Capture: How Big Oil came to dominate Australian politics

What: In conversation with Lyndal Rowlands.

When: 6.30pm, Wednesday, 14 August,

Where: Online

Registration: https://events.humanitix.com/byron-writers-festival-passes-2024/ticketsFREE: Australia’s Biggest Book Club with The Australia Institute

What: Join Royce Kurmelovs as he talks about his new book, Slick, with Australia’s Biggest Bookclub.

When: 11am (AEST), Friday, 30 August

Where: Online

Register: https://events.humanitix.com/byron-writers-festival-passes-2024/tickets

We’ve also got things cooking in Darwin, Canberra and Adelaide. If you’re in Sydney and Melbourne and want to organise something, let me know and we can sort something out.

Before You Go (Go)…

Are you a public sector bureaucrat whose tyrannical boss is behaving badly? Have you recently come into possession of documents showing some rich guy is trying to move their ill-gotten-gains to Curacao? Did you take a low-paying job with an evil corporation registered in Delaware that is burying toxic waste under playgrounds? If your conscience is keeping you up at night, or you’d just plain like to see some wrong-doers cast into the sea, we here at Raising Hell can suggest a course of action: leak! You can securely make contact through Signal — contact me first for how. Alternatively you can send us your hard copies to: PO Box 134, Welland SA 5007

And if you’ve come this far, consider supporting me further by picking up one of my books, leaving a review or by just telling a friend about Raising Hell!