Raising Hell: Issue 84: Encouraging the Careful Use of Petroleum Products

"My belief is, we will, in fact be greeted as liberators" - Dick Cheney, former Vice President and head of Haliburton, Meet The Press with Tim Russert, March 16, 2003

Back in May, the Walkley Foundation announced that it would not be renewing its partnership arrangement with Ampol, one of Australia’s oldest oil companies. Officially, the partnership began in 2022, but ties between the most prestigious award in Australian media — akin to the Pulitzer in the US — and the petroleum industry go back more than half a century. Founded in 1956, by Sir William Gaston Walkley — as discussed in Raising Hell: Issue 81 — the awards served as a convenient means for Australia’s John D. Rockefeller to identify and recruit future public relations talent.

This relationship has long been held up as an example of the historical relationship between Australia’s media corps and the petroleum sector. Now, thanks to Raising Hell’s paying subscribers, we have documents that show how this relationship was actually more pervasive than thought.

But before we get to these materials, it’s important to first understand the context. Today, fossil fuel producers are generally hated for their role in driving the catastrophic effects of climate change, but it is worth remembering that in the heady days of the 50s and 60s, they were treated as heroes. During World War II, Australia had nearly been cut off as imperial Japan stomped its way south through Asia. As a country heavily reliant on oil imports, Australia was hugely vulnerable if its supply lines were to be cut. In the aftermath, the country’s political leadership were desperate to achieve what they called “energy independence” — the creation of a local oil industry to supply the nation’s fuel needs — and so the activities of men like Walkley were framed as a patriotic undertaking.

To help win public support, the industry set up the “Petroleum Information Bureau”, modelled on an equivalent organisation in the UK. It was 1952, a year before oil had even been found in Australia, and a whole decade before anyone would successfully achieve commercial production. The Bureau’s stated mission would be to “disseminate in Australia accurate and authoritative information about oil” and it would be organised under a council made up of the chief executives of its member companies, which in turn oversaw a public relations committee made up of directors and senior executives drawn from within this membership.

The Bureau, eventually, operated out of a ground-floor storefront office in Melbourne’s CBD and operated much like a Scientology outpost offering free personality tests and newspaper-slinging socialist agitators. It fielded questions from the public and the press, distributed free literature and published the free quarterly magazine, Petroleum Gazette.

To get it up and running, the Bureau built itself a vast library from with help from local operators and their international counterparts. According to a write up of its history by John M. Flower — a former Bureau director and a senior figure within the Public Relations Institute of Australia — published in the Asia Pacific Public Relations Journal in January 2007, this included “material on economic matters, public affairs, other energy supply sources, and about the petroleum industry itself, its entrepreneurs, scientists, engineers and a manu of other specialists”. According to Flower, the Bureau maintained extensive mailing lists that included: “Australian parliamentarians, secondary schools, newspapers, radio stations, public libraries and all relevant state and federal departments and agencies, trade associations, magazines, university faculties, trade unions, embassies, research bodies and interested individuals.” It also supplied copies of publications to its member companies and organisations overseas, including oil industry journals.

“So began what was to become a library matched in Australia by few in any other industry bodies (as distinct from professional societies and research institutions),” Flower wrote.

It remains a mystery what happened to this archive or what the materials it may have held addressing the greenhouse effect. What is plain, however, is the extent to which the Bureau sought to recruit journalists to run its operation. In one instance, the Bureau hired Dudley Pilcher, a financial editor of The Argus, former Canberra correspondent for The Age and Australian correspondent for The Economist to head up the organisation until his death (Pilcher’s pronouncements on the state of the Australian oil industry also curiously turn up in CIA media monitoring briefs). Later, the Bureau would commission journalist Clive Turnbull to produce an illustrated history of the oil industry titled “This Age of Oil”.

The Bureau did its job until 1970, when things began to change for the industry. Where once the petroleum producers were noble patriots, their executives increasingly found themselves under attack as the public mood soured. Oil spills on the scale of Torrey Canyon were increasingly making headlines, and a plan to drill for oil on the Great Barrier Reef had mobilised both the Australian Conservation Foundation and the union movement against industry. In response, the executives understood they had to do something or risk losing control of the narrative. For this purpose, they formed the Petroleum Industry Committee on Environmental Conservation.

As it formalised, this committee rebranded as the Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Executive (PIECE), which functioned as a highly-specialised public relations shop, with the express purpose of quelling public dissent on environmental matters. To get things rolling, the Bureau placed a 24-page insert into the 1971 Australian edition of The Reader’s Digest titled: “Respect for Our Environment”. Meanwhile, PIECE began to hold seminars in Australian capital cities addressing pollution issues, featuring addresses by political figures like Joh Bjelke-Petersen and the director of the Tasmanian Environmental Protection Authority.

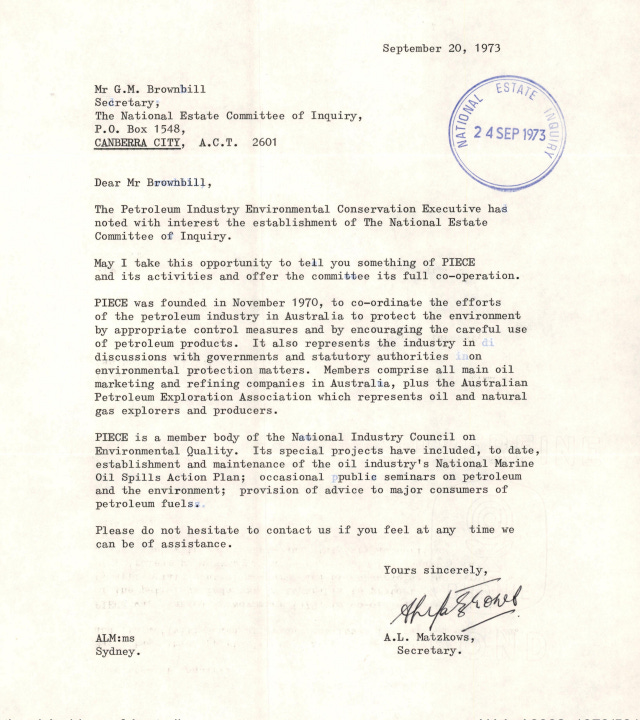

Importantly — and in another example of how the industry sought to poach and cultivate relationships with media — the industry sought to recruit a former Courier Mail reporter, Aaron Mastzkows, to serve as PIECE secretary.

There a currently few documents detailing Matzkows’ life and work, but he served as the Queensland District President for the Australian Journalists Association, the journalist’s union of the day and forerunner to the Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA). It is also not clear when or how Matzkows was recruited, or what the precise arrangement was. Records show Matzkows resigned from something in the early seventies. What is clear is that PIECE coordinated closely with Australia’s oldest running oil industry association:

What this speaks to, I think, is the extent to which Australian journalism has long been treated by industry (and governments) as little more than training ground for future public relations officers. It is perhaps telling that, on the other side, storied reporters eventually came to the point where the pay and conditions meant changing teams became attractive. Oil means money, in any language and that, perhaps, is why it has been so hard to untangle one from the other.

‘Slick is clinical but fun (‘if pumping carbon into the atmosphere could be compared to pissing in a swimming pool…’) and Kurmelovs strikes the right balance between journalistic and conversational. We may be at a tipping point: the next generation —whose future the lobbyists sold—is learning to mobilise, and shareholders are voting down weak climate transition plans. For readers interested in how the system hinders change, this is a timely book.’ — Books+Publishing, 11 June 2024

For the period of 18 June to 2 July…

Reporting In

Where I recap what I’ve been doing this last fortnight so you know I’m not just using your money to stimulate the local economy …

The events page at www.slickthebook.com.au is now live and being updated regularly as new events are locked in. In this last fortnight, it’s been confirmed that The Australia Institute will have me on for Australia’s Biggest Book Club — register here. There are potentially others on the way with the Australian Democracy Network, an Adelaide launch on the cards and potentially something in Canberra, so check back regularly.

BOOK LAUNCH: I’ll be launching my upcoming book Slick at Byron Writers Festival 2024 in August. I have it on good authority that the launch will be open to the public, so if you’re in the Northern Rivers area, swing by! Full program information here.

But that is not the only thing: you can also catch me in conversation with climate scientist Joelle Gergis, author of a quarterly essay, Highway To Hell where we’ll be talking about the end of fossil fuels in Australia. You’ll find ticketing information here and session details here.

I know things have been a bit quiet lately, but that’s because I’ve been furiously working away in the background to put together a series of stories that I am expecting will start to run from the end of July and on into August. There’s also some exciting new collaborations on a cross-border investigation I’m keen to reveal — so don’t go anywhere. It’s going to be a big couple of months.

Before You Go (Go)…

Are you a public sector bureaucrat whose tyrannical boss is behaving badly? Have you recently come into possession of documents showing some rich guy is trying to move their ill-gotten-gains to Curacao? Did you take a low-paying job with an evil corporation registered in Delaware that is burying toxic waste under playgrounds? If your conscience is keeping you up at night, or you’d just plain like to see some wrong-doers cast into the sea, we here at Raising Hell can suggest a course of action: leak! You can securely make contact through Signal — contact me first for how. Alternatively you can send us your hard copies to: PO Box 134, Welland SA 5007.

And if you’ve come this far, consider supporting me further by picking up one of my books, leaving a review or by just telling a friend about Raising Hell!