Raising Hell: Issue 86: Here's a little gas-fired fantasy

'[...]More dangerous are the common men, the functionaries ready to believe and to act without asking questions.' - Primo Levi, 17 February 1986

At the start of the month I published what was a pretty significant story in the August edition of The Monthly. Due to the excitement of the last two weeks, it’s also possible it has been somewhat overlooked between launching Slick at Byron Writers Festival and trying to get the word out — a special thank you to all those who sent in photos of the book in stores, bought a copy and devoured it. Now that I can take a breath, I want to pull the camera back a little to talk about how this story was put together and the significance of what was found, no less than because it was funded by Raising Hell’s paying subscribers.

The first thing, I think, is that it broke a story — evidence that the Australian Gas Association (AGA) was well aware in 1972 that burning gas in homes was a health hazard that could cause breathing problems, even as it played down the risk to avoid derailing a massive expansion of their industry. The source for this is a contribution, or several contributions, by Hans Hartmann, an industrial chemist who served as AGA Chief Technical Officer and a prominent figure across several groups working on pollution issues at the time.

Keen readers of Slick will also recall that Hartmann features a significant character, and someone I am broadly sympathetic to as a historical figure. In this specific instance, his crucial contribution was a 1967 article directly addressing the issue of “Oxides of Nitrogen and the Gas Industry” wherein Hartmann appeared to minimise the potential risk of harm. What makes this significant, in a newsroom sense, is the added dimension this adds to recent campaigns by environmental groups looking to highlight the potential health effects of burning gas inside the home as part of a broader effort to phase out these connections and encourage people to go electric. If in the past campaigners have suggested industry was cavalier with people’s health, we now have it in writing — lawyers looking for class action ideas, take note.

But the implications of this also run deeper. As I learned from climate transitions scholar Marc Hudson while research Slick (you should check out Marc’s project All Our Yesterdays) the health risks posed by burning gas in the home became a club to be used by the coal industry against the gas guys. If the gas guys were going to keep talking about how bad coal was for the climate, the coal guys threatened to start talking about how burning gas in the home gave people breathing problems. Faced with a choice between being a team player or civil war, the gas guys generally fell into line.

The fact this wasn’t top of the story owes much to the way longform and literary journalism works — you need to build up to the big reveal. But even in a story a couple thousand words long, I still didn’t have room for additional detail like the one above — an indicator of what the last two years of research has been like. What was published under the headline Pipeline to Power had been knocking around my skull for the better part of six months. I initially pitched it under the headline, “How fossil fuel companies taught Australians to love gas” — which probably says something about how my time freelancing for VICE poisoned by brain. It was also a story that began with the still-bleeding corpse of all those darlings I had knifed in the production of Slick. The offcuts and leftovers in the initial round of materials I obtained on the book laid a foundation that was then supplemented with additional research, funded thanks to the generous support from paying subscribers to Raising Hell. This involved flying to Sydney and Canberra to look through materials and paying for the digitisation of other documents in archives I could not reasonably afford to travel to.

Needless to say, what I learned seemed incredible. Much of the focus on the story was the way in which public relations was essential to the expansion of fossil fuel production, and how gas executives learned to wield influence — sometimes with devastating effect. If much of my work to date has focussed on the intersection of class, finance and, now, climate change, a frequent subject has been social movements. Back when I wrote The Death of Holden, for example, I picked up on the proto stages of The Anti-Poverty Network campaigns that, eventually, jumped across to the east coast and led to the Robodebt Royal Commission — an event I also covered in Just Money. Rogue Nation — which in hindsight should have been titled “Rogue’s Nation” — was also an attempt to view how these forces were fuelling demagogues like Pauline Hanson.

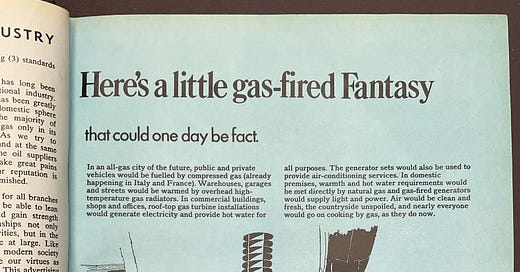

What was remarkable from the gas industry materials was the extent to which the early oil and gas producers can be thought of as a social movement. As I recount in Slick, considered as a group, what we have is an organised corps of people responsible for the identity and future planning of an industry, who operated with clear short and long-term goals. Short term, the objective was to find oil (gas was always a consolation prize). Long-term, they wanted to grow filthy-rich. To get these things, they formed themselves into associations that functioned as pro-business unions; representing their interests to government and the public even as they concealed the internal frictions and feuds in service to their overall goals. They were also very effective — and offer lessons for their critics. When it comes to the gas industry specifically, and where things depart from the story told in Slick, it is important to understand that these people existed prior to the first oil find but sought to reorganise themselves from the ground up in order to take advantage of a major transition. As I write in The Monthly, this took these executives as far afield to the United States where they trained with, and took inspiration from, their American cousins. More dramatically, they went so far as to pen a whole manifesto:

The other remarkable thing about this, was the extent to which public relations formed the connective tissue of the industry. The ad men, the spinners, the marketing gurus, the lobbyists, the designers — these were the shock troops of American, and later, Australian capitalism. Speaking of this, I have recently finished up working on another story in collaboration with international outfit DeSmog that examines how the global oil industry’s preferred public relations firm, Hill & Knowlton, helped bring sophisticated public relations practices to Australia — and how the Australian oil industry relied upon corruption to resist what could have been (and arguably was) a nakedly neo-colonialist moment. I can’t say much more at this stage, but I will be talking more about that story when it goes live.

Today the gas industry is considered a fundamental feature of the Australian economy and the country vies with Qatar and the US for the position of top LNG exporter. The export of gas and other fossils contributes massively to climate change, but these people are considered untouchable. This state of affairs, however, hasn’t always existed. To get there, those with the will to power had to work for it and it was a tangled web of disinterested professionals who helped them carry it off. They were the ones who articulated the vision, who presented it to the public, and who created a spectacle which laid the groundwork for change. In effect, these communications specialists could be thought of as extremely well-paid activists with excellent design skills, who embarked on a half-century long campaign with laser-like focus on their ultimate goal — if you’re looking for an example, take a look at this wild industry instructional video produced for the South Australian Gas Company.

They were, arguably, highly successful — and still at it. Put into the context of climate change, it is important to understand that neither did this existential threat come out of nowhere. It wasn’t just the unfortunate by-product of industrialisation — it was the product of a determined delaying action by pro-business activists who remain well organised, even if they don’t always operate with finesse. From an investigative standpoint, this insight belies the need for transparency and accountability regarding the activities of those responsible. This, for what it’s worth, is also why I have been published excerpts from the primary sources that underpin Slick on the book’s website covering the Origins, Influence and interference by industry. Not only is this to help establish the veracity of my own reporting — a favoured industry communications tactic is to never address critical media directly, but to instead go around bad-mouthing the reporter to anyone who will listen to undermine their credibility — but it allows interested members of the public, researchers and civil society to draw on this materials in their own work when seeking to hold the powerful to account.

And, you know, if you read these materials and know more about them, or happen to have a bundle of grandpa’s old letters and documents in the garage, get in touch. I’d love to know more.

Events

Now the book’s live, there will be events — I hear you love events, so I got ‘em in droves. Below are a list of those which are confirmed. Check the website as I’ll be putting up the details of new events as they’re locked in.

FREE: Australia’s Biggest Book Club with The Australia Institute

What: Join Royce Kurmelovs as he talks about his new book, Slick, with Australia’s Biggest Bookclub.

When: 11am (AEST), Friday, 30 August

Where: Online

Register: https://events.humanitix.com/byron-writers-festival-passes-2024/tickets

THIS THURSDAY: ADELAIDE LAUNCH: Slick: Australia’s Toxic Relationship with Big Oil

What: Join Royce Kurmelovs for the launch of Slick, with opening remarks by Federal Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young and hosted by Walter Marsh, author of Young Rupert.

When: starts 6pm (sharp), 5 September

Where: The Wheatsheaf Hotel

Tickets: FREE — but registrations essential. Register here.

We’ve also got things cooking in Darwin and Canberra. If you’re in Sydney and Melbourne and want to organise something, let me know and we can sort something out.

Before You Go (Go)…

Are you a public sector bureaucrat whose tyrannical boss is behaving badly? Have you recently come into possession of documents showing some rich guy is trying to move their ill-gotten-gains to Curacao? Did you take a low-paying job with an evil corporation registered in Delaware that is burying toxic waste under playgrounds? If your conscience is keeping you up at night, or you’d just plain like to see some wrong-doers cast into the sea, we here at Raising Hell can suggest a course of action: leak! You can securely make contact through Signal — contact me first for how. Alternatively you can send us your hard copies to: PO Box 134, Welland SA 5007

And if you’ve come this far, consider supporting me further by picking up one of my books, leaving a review or by just telling a friend about Raising Hell!