Raising Hell: Issue 89: On Climate Change As A Class Issue

"I'm a warrior for the middle class!" - former US president Barack Obama, on the campaign trail in Ohio, 22 September 2011.

Truth is, I don’t really like talking about my upbringing. Teenage-hood is an awkward enough experience at the best of time, let alone growing up in a place like Salisbury Park on Adelaide’s northern fringes. Telling people stories from this time feels wrong. There is always this feeling of doubt when I retell stories about growing up; like I’m simultaneously making something up and holding something back. What if, thanks to time, distance and the function of memory, I’ve exaggerated things? What if I’m leaving things out because it sounds to much? Much to my frustration, I often find myself repeating that familiar northern suburbs refrain: yeah, sure, it could be rough, but it wasn’t all bad.

I have included memories from when I’ve grown up in my work. There was the time in The Death of Holden for instance, where I briefly mentioned how a friend of mine who had left school early passed out in the bathroom of the café she worked due to sheer physical exhaustion. These days I joke about how the biggest celebrity to come out of my neighbourhood was David Hicks, Australia’s first foreign fighter who got picked up the US military standing by a tank in Afghanistan and ended up locked up in Guantanamo Bay. Sometimes I tell people how my best-friend’s stepfather threw him through a television one night, forcing him to go to live with his biological father and how, to pay room and board, he had to tend the cannabis crop which was accessible by a hidden compartment behind the dishwasher in the kitchen.

If I’m feeling really comfortable, I might tell you about the time my family helped an 18-year-old Pakistani guy who was stuck on a bridging visa — not for any ideological reason, but just because it was the right thing to do. That one’s a long, complicated story, one I may actually tell in print eventually, but one with a sad ending. A few months after he was forced to return home to Karachi, three gunmen shot him in his sister’s home.

Then there are the dark stories, like how the other kids used to come hang out at our place because, all things considered, it was peaceful and safe. In high school these same people began to relentlessly bully my sister. It took me a decade-and-a-half to understand they had been victims of childhood sexual abuse and their actions were, in turn, the product of deep, profound trauma and betrayal.

I have, at times, told these and other stories when someone needs to be shut down for acting like a prick, and to people I trust, occasionally over beers. Talking about these sorts of things, however, does generally make me uncomfortable. I may have been born into a family of migrants that left behind war and conflict, but I am not a person of colour, Indigenous or LGBTQI. I don’t have to manage complex mental illness. And for all the bad times I can point to, there were also good, happy times. We had two parents who, for all their faults, loved us. My mother taught us to read young, and my father showed us how to work. I still have many friends from that time and we had fun together. Some have left, others have stayed, and some have gone on to form families of their own. My graduating class produced more PhD’s than others in recent memory.

But then, sometimes, when I encounter people from much higher up the income spectrum and get talking to them about this sort of thing, they can respond in odd ways. For some, it’s a condescending form of pity. Others respond with a voyeuristic keenness that treats this sort of thing as poverty porn. Another group simply have their deepest prejudices confirmed. These people, I find, hear but don’t see. Yes, there is hurt. There’s pain and trauma, and sometimes the weight of these experiences break a person, or twist them until they too resemble monsters. But not always — and not even often, in my experience. Few seem to recognise the nobility of people responding to difficult circumstance with resourcefulness, adaptability and solidarity. There are good reasons why poor and working class kids, on average, do better in university — and perhaps, in their professional careers when given a chance — than their counterparts from privileged backgrounds. Yeah, sure, we can be coarse on but by god we’ll get shit done.

So what’s all this got to do with climate change?

Two weeks back, The Australian Institute hosted me for an event in Canberra where I talked about what I found in my book, Slick. Across its pages, I detail how an relatively small group of industrialists — a group of elites — organised themselves over a period of decades to shape policy and the cultural environment to serve business interests at the expense of the public. It was a great event but when a clip was shared on social media, the response from a couple of users proved interesting. In short, they pointed to the jacket I was wearing and how articulate I was to write me off as an inner-city elite talking down to the working classes.

I don’t want to blow this out of proportion. When you do journalism, you get kick back. It’s an occupational hazard — like the heightened risk of cancer when working in a oil refinery or driving a tanker. In my time, I’ve been accused of many being many things; a jealous son of the Australian public school system; an entitled private school kid with a born to rule worldview; a Liberal party apologist; a radical left Greenie; a centrist; a national traitor; a neoliberal; a Muslim; English; a fan of JD Vance. This was, for the most part, a mild encounter with a common, vicious trope used by climate deniers to paint anyone with concerns about climate change as some kind of jet-setting, Davos influence peddler. The joke, however, was very much on them. The jacket I wore had been borrowed from a friend earlier that evening as I forgot to bring a coat to Canberra. I currently live in a regional area — albeit, one that serves as something of a sub-tropical Martha’s Vineyard. It is also true that I can string a sentence together because I have an education, but then I remain a precariously employed freelance journalist.

Now my usual response to anyone who demands I perform my politics or identity is fairly blunt. Professionalism and common sense, however, meant I didn’t respond like a good son of Adelaide’s northern suburbs. In defying my base instinct to put these people on blast, there was, I felt, an opportunity to use this as a provocation to actually think through some bigger questions.

Climate change, as far as I’m concerned, isn’t just a class issue, it is the class issue. Naturally, I said as much in a snappy post to social media, where I also said that if any editors out there were paying attention, I could write a cracker essay unpacking this. Almost instantly, I regretted this decision, mostly because if anyone actually followed up, I would then actually have to do it. For a few days, I thought I had gotten away with the caper when no response came, but then an editor of a smaller outfit hit me up. I didn’t say ‘yes’ (sorry!) but I didn’t say ‘no’ either, and the idea has kept niggling away at me.

If I were to group my stray thoughts together into something semi-coherent, the way I see it, there two parts to this: cause and effect. If class defined by your relationship to work, and climate change is a class issue, work has to have something to do it. And with the impacts from climate change hitting those with the least, hardest, it is no stretch to suggest those who engage in climate denial are engaged in class war. Oil, gas and coal translates to ‘money’ in any language, and those defending their interest are aligning themselves with the richest corporations in human history. There is, perhaps, no purer representation of capital. These are people who, with an eye on their share price, are currently expanding their operations at a scale which will harm their workforce— and exacerbate an existential threat to humanity. And when they are done, they will shut it all down — as I report in Slick, this has long been the plan — salute the workforce for their service, and leave them to their fate — as I also show The Death of Holden.

When it comes to talking about these sorts of issues, I have long been conditioned to show not tell, to use metaphor and clever literary devices to communicate meaning — that is to trust readers to interpret my work without being spoon-fed. Recent experience, however, has made it clear that the ideas that inform my work are not always well understood, and so I should probably make an effort to be a little more explicit in grounding it, especially as variations of these ideas have kicking around the back of my skull for a while. Because I’m kind-hearted, lazy and merciful — no one wants to be slapped with a 3000 word essay in their inbox on a Tuesday morning — the current plan is to serialise my thinking on this over an issue or two of Raising Hell. This way I can give myself a break between all the other things I’m supposed to be doing to make a living. I’m also not going to get super crunchy with it, so you can rest easy knowing you won’t be thwacked with a weighty tome like Thomas Pickety’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century. At the end, the individual parts may add up to a cohesive whole. Or not. Either way, we might just all learn something.

Good Reads

Because we here at Raising Hell know how much you love homework…

Emily Lynell Edwards, writing in Type Magazine, has a good literary theory essay exploring “The Death of the F*ck: Neopuritanism and Commercial Fiction.”

"Many books about climate change are worthy but dull. Slick, however, is as readable as it is shocking." - Richard Denniss, The Australia Institute, writing in The Conversation.

Reporting In

Where I recap what I’ve been doing this last fortnight so you know I’m not just using your money to stimulate the local economy …

‘In Australia, a New Way to Avoid Decommissioning Oil Fields: Call Them Carbon Capture Projects’ (Drilled, 7 September 2024).

‘Why economists want negative gearing reform’ (The Saturday Paper, 5 October 2024).

Events

Now the book’s live, there will be events — I hear you love events, so I got ‘em in droves. Below are a list of those which are confirmed. Check the website as I’ll be putting up the details of new events as they’re locked in.

Darwin: Darwin Book Launch

What: A book launch. In Darwin.

When: October 17, 5.45pm

Where: Darwin Railway Club

Register: https://www.ecnt.org.au/slick_darwin

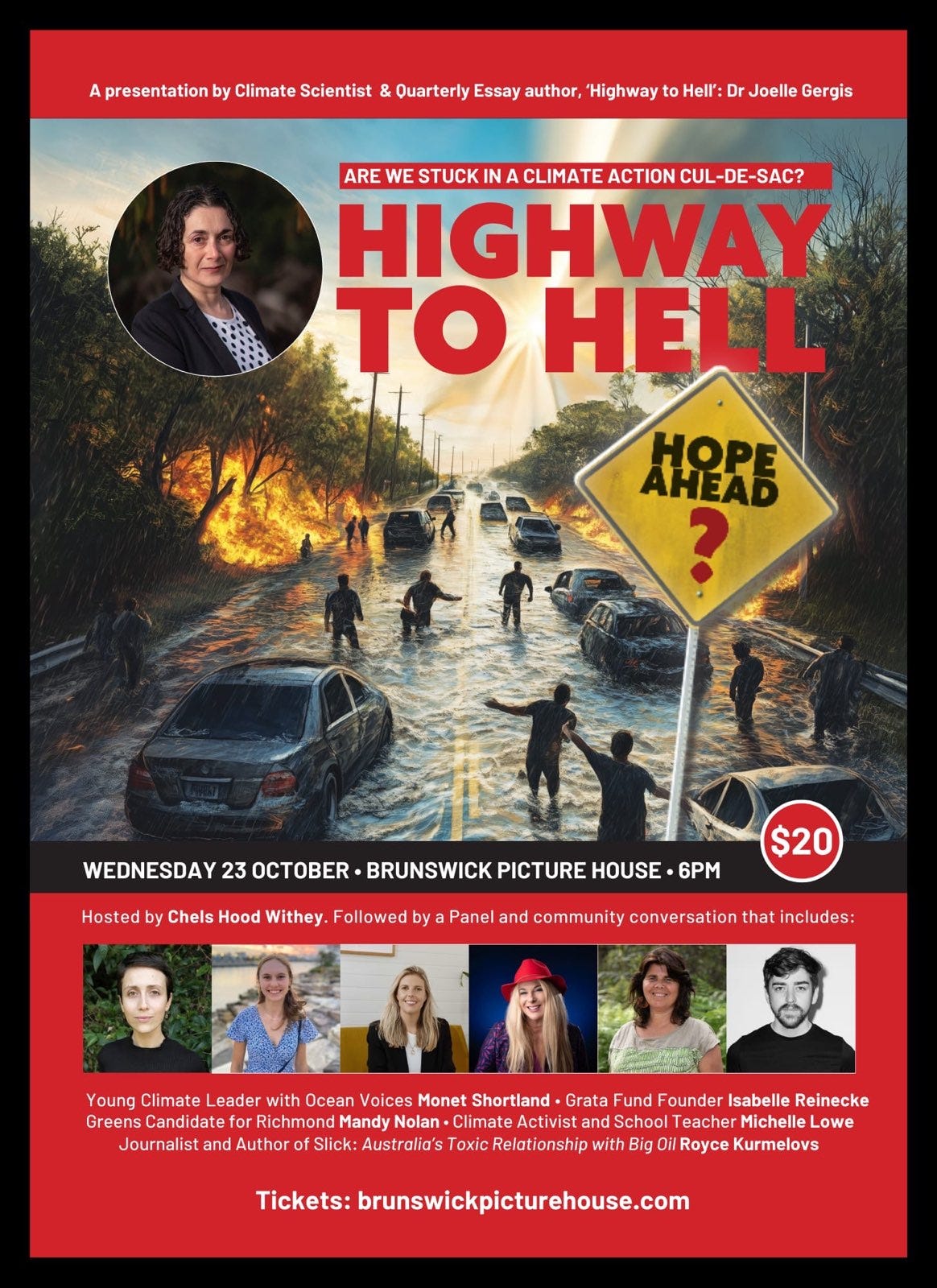

Brunswick Heads, NSW: Highway To Hell

What: Presentation by climate scientist Joelle Gergis, followed by a panel discussion. Tickets $20.

When: 6pm (AEST), Tuesday, 23 October

Where: Brunswick Picture House, NSW

Register: https://brunswickpicturehouse.com/highway-to-hell-23-oct/Canberra: Anthropocene of the Crime

What: Michael Brissenden’s latest novel is a propulsive thriller; Royce Kurmelovs’ new book is a corporate exposé - true crime at its best. Both are also tales of the climate crisis. David Lindenmayer joins them to consider the novel ways our writers are helping us understand our planetary calamity and chart a way forward.

When: 10.30am (AEST), Sunday, 27 October

Where: Representatives Chambers, MOAB

Register: https://tickets.canberrawritersfestival.com.au/Events/Anthropocene-of-the-Crime

We’ve also got things cooking in Melbourne and Perth, so check the website for new events.

Before You Go (Go)…

Are you a public sector bureaucrat whose tyrannical boss is behaving badly? Have you recently come into possession of documents showing some rich guy is trying to move their ill-gotten-gains to Curacao? Did you take a low-paying job with an evil corporation registered in Delaware that is burying toxic waste under playgrounds? If your conscience is keeping you up at night, or you’d just plain like to see some wrong-doers cast into the sea, we here at Raising Hell can suggest a course of action: leak! You can securely make contact through Signal — contact me first for how. Alternatively you can send us your hard copies to: PO Box 134, Welland SA 5007

And if you’ve come this far, consider supporting me further by picking up one of my books, leaving a review or by just telling a friend about Raising Hell!