Raising Hell: Issue 90: It's called 'f*ck you money'

"Everybody has plans until they get hit for the first time," - Mike Tyson, 19 August 1987

A few years back American actress Lucy Liu gave an interview where she laid her theory of fiscal success. The genesis, she said, was her father, who had taught her how “everything’s a business” and so, when it came to work, the smart move was to have a large sack of cash on hand at any given time.

“I worked a lot to just have money,” Liu said. “It’s called ‘fuck you money’ and if you have it and something’s not working out, and they say you have to take this job or otherwise you get fired, you’re like, ‘fuck you’.”

At the time the idea of a “fuck off fund” was celebrated by girl-boss Pintrest feminists and online grind-set hustlers as the skeleton key to late-era capitalism. What was the old-world idea of “have savings” was born anew as a savvy strategy for basic financial survival.

There’s nothing wrong with what Liu is saying in principle; moving through life certainly is easier when you’re sitting atop a big pile of cash. The problem is the worldview that underpins it. Making money from money isn’t so hard once you’ve got it. For the vast majority of people, the problem is making a little money in the first place — just ask anyone on social security.

Being poor is work to begin with, and the whole point of a social security system was to provide the same basic function as Liu is describing. If you’re suddenly laid off, in a domestic violence relationship, living with abusive parents or trying to upskill with education, social security was supposed to ensure you still had agency, that you could escape. Today just meeting the challenge of the social security, owing to moral panics about fraud and Dole Bludgers, is a full time job alone. In Australia, those forced to rely on this subsistence income are fed into a private, for-profit system of “Service Providers” that seeks to monetise poverty. In this relationship, the service provider holds the whip hand, and their authority is total.

This is why wealth is the wrong starting point when talking about class. Class, as I have written before, is not primarily about money, or mullets, or a taste for lattes. Class is about work and your relationship to it. It is about who does the work, and who calls the shots. It is the measure of your ability to decide whether you work, when you work, how often you work, how fast you work, who you work for and at what rates. Do you get to spend your productive time trying to get the Dutch government to deconstruct a historical landmark so you can move your superyacht, or are you the person pissing in bottles so that same guy can go to space? Who, exactly, is taking on the risk when carrying out a task in your workplace? Is your manager getting down on hands and knees to clean behind a fryer for no good reason? Or are they making you do it? Can you clock off at three in the afternoon for a round of golf without being fired? Or do you need to stick around for another hour on a Friday to do a rush job on that thing that was decided last minute? If you quit or are fired tomorrow because of racism, or a sexual assault, or outright abuse, or any number of reasons, is that going to trigger a cascading series of events through your life that will end in you becoming homeless? Depending how you answer these sorts of questions, you’ve got a much clearer understanding of where you fall in this hierarchy.

Thinking about things this way offers a certain clarity. Take, for example, an independent trucker. Society might tell her she’s a ”small business owner”, but that is only true in the strictest legal sense. Unless she outright owns her own rig and the real estate needed to house it overnight, the debt and depreciation on her set up means she will face increasing pressure to take any job, anywhere, from anyone, no matter how far, how tight the turnaround or how much of a racist prick they are. Thinking this way also helps to understand how the middle has been hollowed out of the economy to the point where even once high-status jobs like law, architecture, medicine and engineering have had their conditions eroded over time. Yeah, sure, the partner may still get to go for a long lunch, but it is strongly implied the solicitors actually writing the advice — the productive labour — are expected to be in before 8am, not to get up from their desk through the day, and stay long after 5pm to keep billing in six-minute increments. There are obvious differences — whether in identity, worldview, the nature of the work involved, and expectations of upward social momentum — but in this day and age, chances are “worker-bee” lawyers are materially going to have more in common with the trucker than the senior partner, at least in the first instance.

Moving away from the traditional stereotypes of working class jobs and the professions for a moment, this way of thinking also helps understand on demand labour and the precarity of our moment. If you’re an Uber driver, for instance, you might get to pick your hours, but if you don’t want to waste your money on petrol and repairs, you’re going to have to work — and you better be nice about it. Good luck making a living with a four-star rating.

Something similar can be said for the “glamour” trades like art, film, music, literature and journalism, where the overwhelming majority of success is enjoyed by those with rich parents. Yeah, sure, platforms like Twitch, YouTube, Substack and Onlyfans have democratised access the arts in some respects so that now everyone gets the chance to make a career-killing mistake by voicing their opinions online and in public. The catch is that only the top tier of creators ever really earn. The rest, the wanna-be’s, don’t have the time or money to acquire the skills, technique, equipment, production skills and support teams which underpin “talent” to make it happen, and so just form part of the churn on which Amazon can sell products.

Money and wealth may not be the factor in determining class, but the security of a large bank account and a real estate portfolio is certainly helpful to dealing with the verisimilitudes of life by guaranteeing agency. Having the ability to walk away — that is, having “fuck you money” — is helpful to protect from the unhinged demands of a boss who thinks they actually do own you for eight-plus hours a day. If you’re not so lucky, you’ll find yourself living in an insecure world which hinges on keeping the lord of the manor pleased — a contemporary “Downton Abbey with iPhones”, as political economist Mark Blyth once put it.

Wherever you fall in this spectrum, the issue is not about personal morality — for what it’s worth, I, personally, like Lucy Liu and her art. This is about describing the human environment in which we operate. The exception is, of course, if you’re a Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk or Peter Thiele or Gina Rinehart, in which case I don’t know why you’re reading me to begin with. These are individuals whose personal bank account has its own gravitational pull. Theirs is global “fuck you money”, where the goal isn’t to use this wealth to defensively buttress against the volatility of life, but to go on the offensive and remake the world in their own image. They are single adults with the resourcing of small nation states, a status that makes them, their mental health and their personal whims on any given day a threat to democracy.

It is also important to remember that the eye-watering plenty enjoyed by these figures has come largely at the expense of everyone else alive. This wealth was not secured through hard work — that’s for suckers — but by cornering parts of the rentier economy, generous tax concessions, taxpayer subsidies, and a general process by which the cost and risk associated with production has been shifted onto their workforce, even as capital has extracted ever greater shares of the profit. This is true right across the world, but here’s a handy chart to help visualise how Australians have been squeezed over the last half century:

This squeeze, mind you, applies to the middle classes as much as it does to the working class, which has found itself under increasing stress as this process plays out. Financialised economies are geared to target middle class households in particular, to encourage them to take out ever-increasing amounts of debt, often in exchange for low quality goods. The result across the board is an extractive economy based on rent seeking, a breakdown in upward social momentum and a trickle down sense of insecurity, precarity and frustration defined by a lack of control over livelihoods and lives.

If the first step is to sketch out class in this way to understand the dynamics of the human environment, the next step is to understand how this connects with the natural environment. If we accept that climate change is caused by humans — and we do, because it is — it is worth then asking what does that mean, exactly? If CO2 is a by-product of production and consumption, something must be out of whack. If that is true, work is implicated.

To get the metal and rock and wood needed to make food and fuel and medicine means moving a whole bunch of people around and having to house them. Making all this happen is the stuff of work, and if something about this is so lop-sided that we are generating an existential threat to human civilisation, that makes that situation very much a class issue. As writers such as Keir Milburn have argued, we can think about growing precarity as the result of capital having found ways to secure a greater share of profits from production, partly by pushing production into overdrive with fewer and fewer constraints. If we can think about work in these terms, we can also think of climate change as the result of capital shifting the cost and risk associated with production onto nature as it seeks to expand its share of profit. As Thomas Oatley and Mark Blyth have also pointed out, this is the basis of the “carbon economy” and the whole post-War set up has built around trying to harness it. A whole suite of institutions grew out of a world underpinned by hydrocarbons, and a group of decision makers drew on the constituencies that formed around these institutions to secure their wealth and influence. That is what we are grappling with today.

Think I’m exaggerating? Pull the camera back a moment and it is possible to see where things were always headed. Consider for a moment how the first issue the nascent Australian oil industry lobbied over was a push to double the government subsidy to encourage exploration. Think about how the founding chair of Australia’s largest oil and gas industry operation was aware there was a risk posed by burning fossil fuels as early as 1969 but helped secure a massive expansion of the industry anyway. Recall how even today the Australian government collects more from student debt repayments than it does through the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax.

In the end though, the joke is on the rest of us. Humanity is inseparable from nature and human civilisation has come to flourish in a particular ecological niche. As the natural systems around which we build our lives — the clockwork nature of the seasons and the narrow temperature bands in which we build our cities — increasingly break down, we each will bear the cost of the risk-shifting exercise that made global-scale “fuck you money” possible.

But that is a subject for next time.

Good Reads

Because we here at Raising Hell know how much you love homework…

Amy Westervelt at Drilled has this analysis on the climate movement that’s worth reading, provocatively titled ‘De-fund the Tone Police’.

I’m halfway through Rick Morton’s book, Mean Streak, looking at the Robodebt Royal Commission and the excoriating account of those responsible. It’s good. Buy it.

"Many books about climate change are worthy but dull. Slick, however, is as readable as it is shocking." - Richard Denniss, The Australia Institute, writing in The Conversation.

Reporting In

Where I recap what I’ve been doing this last fortnight so you know I’m not just using your money to stimulate the local economy …

‘Zero-carbon beer is a myth: how to make brewing greener' (The Guardian, 19 October 2024).

Events

Now the book’s live, there will be events — I hear you love events, so I got ‘em in droves. Below are a list of those which are confirmed. Check the website as I’ll be putting up the details of new events as they’re locked in.

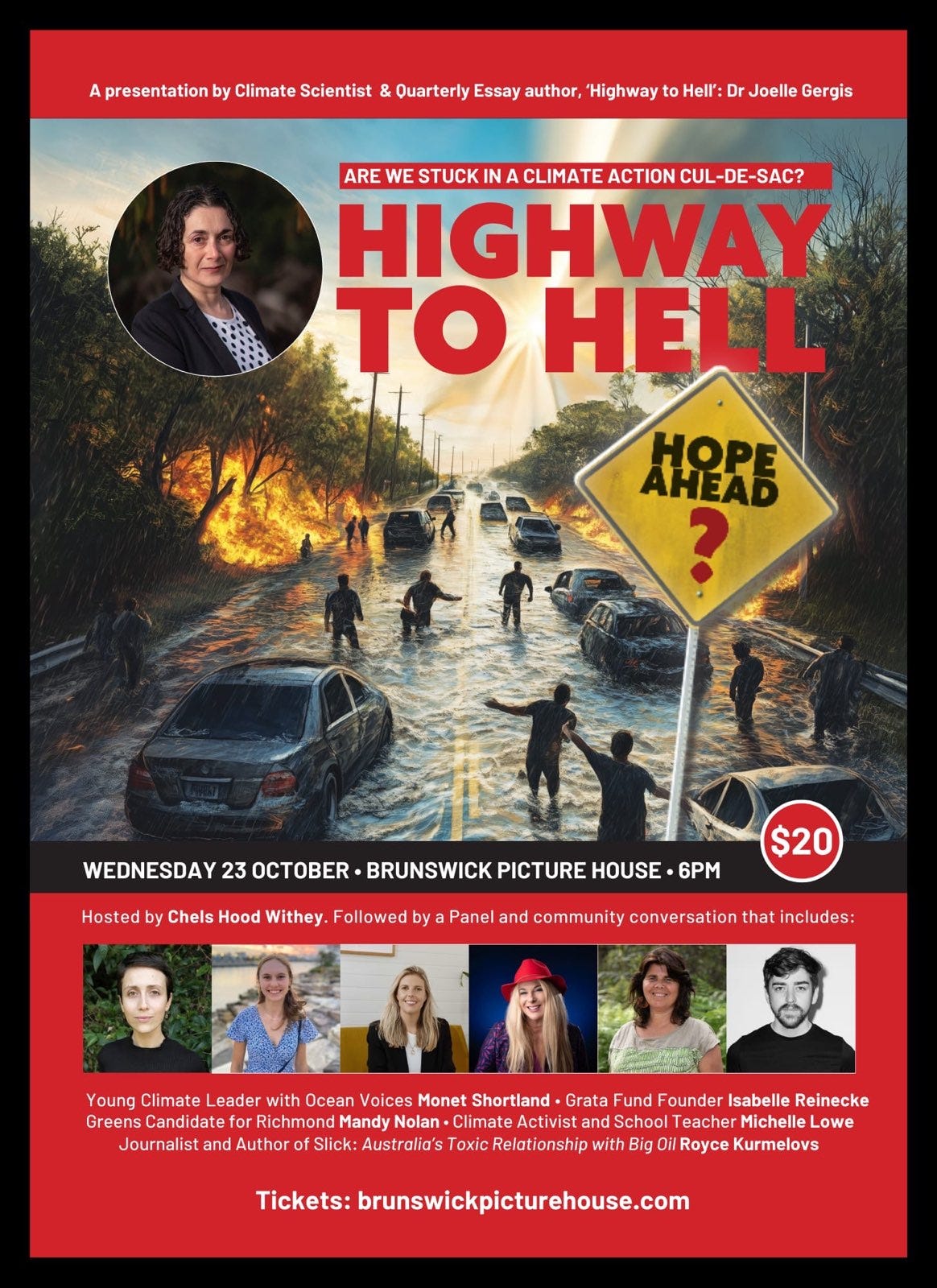

Brunswick Heads, NSW: Highway To Hell

What: Presentation by climate scientist Joelle Gergis, followed by a panel discussion. Tickets $20.

When: 6pm (AEST), Tuesday, 23 October

Where: Brunswick Picture House, NSW

Register: https://brunswickpicturehouse.com/highway-to-hell-23-oct/Canberra Writers Festival: Slick With Royce Kurmelovs

What: For decades, the global oil industry has conspired to undermine international efforts to address environmental devastation. Investigative journalist Royce Kurmelovs’ Slick is a riveting expose of these tactics. Join Royce in conversation with Ron Misen as he traces the story from boardrooms to bushfire ruins.

When: 10am (AEST), Sunday, 26 October

Where: Senate Chamber, MOAD

Register: https://tickets.canberrawritersfestival.com.au/Events/NEW-EVENT-Slick-with-Royce-KurmelovsCanberra Writers Festival: Anthropocene of the Crime

What: Michael Brissenden’s latest novel is a propulsive thriller; Royce Kurmelovs’ new book is a corporate exposé - true crime at its best. Both are also tales of the climate crisis. David Lindenmayer joins them to consider the novel ways our writers are helping us understand our planetary calamity and chart a way forward.

When: 10.30am (AEST), Sunday, 27 October

Where: Representatives Chambers, MOAD

Register: https://tickets.canberrawritersfestival.com.au/Events/Anthropocene-of-the-Crime

Before You Go (Go)…

Are you a public sector bureaucrat whose tyrannical boss is behaving badly? Have you recently come into possession of documents showing some rich guy is trying to move their ill-gotten-gains to Curacao? Did you take a low-paying job with an evil corporation registered in Delaware that is burying toxic waste under playgrounds? If your conscience is keeping you up at night, or you’d just plain like to see some wrong-doers cast into the sea, we here at Raising Hell can suggest a course of action: leak! You can securely make contact through Signal — contact me first for how. Alternatively you can send us your hard copies to: PO Box 134, Welland SA 5007

And if you’ve come this far, consider supporting me further by picking up one of my books, leaving a review or by just telling a friend about Raising Hell!