Raising Hell: Issue 91: A Can of Tuna In The Mud

"I haven't found anybody in seven and a half years shake their fist at me and say 'Howard I'm angry with you for letting the value of my house increase,'" - John Howard, former PM, 19 Sept 2003

Two years ago I was assigned to cover a story that served as a divining rod for the intersection between class and climate change in Australia. A few years prior, a powerful storm had whipped an angry ocean, driving the waves forward until it smashed against the shoreline along Collaroy beach in Sydney’s northern beaches. As the waves licked the landmass, images of swimming pools out back of multi-million dollar properties falling into a raging seat hit the internet with a splash as people indulged in schadenfreude at seeing someone else’s multi-million dollar beachside dream tumble into the surf.

The gloating of those online may be unseemly, but it was a natural consequence of a gaping wealth divide that had opened in Australian society like a chasm. Sydney was, and remains, one of the most expensive housing markets in the world. It was also a reminder that climate change wasn’t just coming for the poor.

In the years and months after this disaster, residents who lived along that strip of houses rebuilt, recovered and organised. With insurance premiums rising, they wanted to build a 7m sea wall to hold back the tides — which is where I stepped in.

The tendency of seawalls to destroy the beach in front of it without ongoing nourishment made this project particularly controversial. Australia’s beaches, I later learned, are a geological marvel. They had all been formed at roughly the same period in the geological record and often behaved like living things. They appeared to inhale and exhale, and changed shape over time. They were fed by the dunes that acted as a buffer between land and ocean but over time Australia had paved over these buffer zones. The dunes where early colonists often erected their shacks where the same where the middle class later built their homes so they could have the waves at their back door. Industrial Australia then followed by building roads and carparks that choked the beaches to allow easier access for a nation built its identity on that pristine white sand.

All of this is what made proposals like the Collaroy so controversial. These big, expensive concrete structures, sunk metres into the sand, were supposed to armour the coastline to prevent erosion but as they broke up the natural processes that created the beach, the sand in front would wash away with time. A trade off was being made to protect the land value of a select group of people at the expense of a public good: the beach.

Climate change had obviously brought additional complications as sea level rise and wild weather would overwhelm these mitigation measure eventually. King Canute at at one time understood this, unlike the last Byzantine Emperor who did not. Constantine eventually learned the hard way that no matter how high your walls, someone will eventually turn up with a cannon.

For their part, the Collaroy residents championing the wall weren’t particularly interested in having a conversation about the futility of holding back the sea in the face of climate chance, and neither was the local council. When I asked the residents for their thoughts on the existential reality of climate change and the potential for an angry ocean to eventually knock on their back door, most side stepped the conversation. In a very human way, their focus was on the short term. The residents had bought in good faith, often in retirement, thinking they would die in their bed with the sea at their back and the sand beneath their feet. All they wanted was to keep the ocean out of their backyard and to maintain the value of their home because they were also aware there was no program to facilitate a managed retreat.

Broadly speaking, there is perhaps no greater fear among the upper classes than the prospect of being de-classed — that is, of being poor again. And to be fair to those residents, they were in a bind. Some real estate agent had sold them a dream even as the risks were apparent. If they ever wanted to move away, they would need to keep the value of their home high enough to facilitate that. The rational thing would be for a local council or state government to agree to buy back the property at some point in a planned, orderly retreat before the ocean made the decision for them.

Local authorities said that was all well and good, but they pointed to the price of housing on the open market, threw up their hands and asked where, exactly, that money would come from. That might need to happen, but really the state government should step in, they suggested. The state government of the, meanwhile, turned around and said it wasn’t their problem. Climate change was already an afterthought for the conservative Perrottet government that then ruled New South Wales and their state was home to the largest coal port in the world. What mattered was money — specifically the need to maximise money coming and minimise money flowing out. And no conservative politician was going to suggest they were week by uttering the words “managed retreated” in public. They were going to built back better after disasters. Every time. Forever.

In the end, the residents got their wall.

Compare this story with the destruction wrought upon Lismore in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales. An old colonial town built at the confluence of two rivers, Lismore has always been a town that flooded — and then everything changed in 2021. First the catastrophic Black Summer Bushfires had torn through the region, sweeping south down into Victorian. The year after, the rain began to fall over Lismore and did not stop until the town was temporarily removed from the map. The image of a house, slathered in petrochemicals and ablaze in the middle of the Lismore flood was perhaps a grim metaphor for the reality of climate change in Australia.

It is hard, perhaps, for those outside the region, and outside New South Wales to understand the significance of this event, particularly as it relates to class, largely due to a lack of context. For a start, the Northern Rivers, as a whole, sits right on the border between Queensland and New South Wales. A train once used to operate, but today the region is entirely car dependant with sparse bus and shuttle services. Lismore itself lies inland, a fifty minute burn west of the Pacific Highway. It is part-university town, part agricultural precinct and part-hippy way-station for those moving through Nimbin. It is also a major service centre, similar to Ballina over on the coast. It is where the kind of people who grow your food, fix your car, build your beautiful homes and make the music you loved live and work. This heady mix has given rise to a sizable population who aren’t the usual constituency for The Nationals whose ten gallon hat has cast a long shadow over the regions. When the flood came, it was these people who were smashed.

This in part explains why, when everything went to hell, the residents of the region mobilised. When it became clear the authorities were overwhelmed by the scale of the disaster and unable to help during the crisis, people from across the region formed their own defacto navy, The Tinnie Army. Some of these people were rich, others were poor, but everyone who brave live electrical lines and polluted floodwater to pull people from rooftops understood that no one was coming to help.

In the aftermath, even as the rain kept falling, there was no market to supply people. There were no clean clothes, no baby diapers, no cat kibble. One woman I later interviewed, Kate Stroud put it simply: “When you’re in a situation where you find a can of tuna in the mud and think that’s all you’re going to have to eat for a little while, your perspective changes.”

Overnight the people of Lismore and the surrounding regions — a whole constellation of towns that never got the same attention — became climate refugees. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, Australia recorded 41,000 internally displaced persons that year — a mind-blowing thought for many Australians who might otherwise think of refugees and asylum seekers as a problem “over there”, wherever that may be. This event brought with it all the same dynamics that tend to follow large movements of people from one region into another. The bulk of those moving from Lismore, needing a place to live, headed out towards the coast, some temporarily, some permanently. Rents began to rise as people looked for places to live; waiting times for services blew out; getting tradesmen to do repairs or construction became near impossible.

Those who struggled to find somewhere else to live and felt forced to return to Lismore were faced with difficult choices. If their home survived, it was uninsurable and any value it held had been knocked out of it. With the state having long cut away the administrative muscle it needed to act, government was slow to move in putting together a buyback scheme. As they waited, many slept in caravans beneath their gutted homes. Some gave up and sought to sell. The people who bought these properties were risking their lives and stepping into an insurance nightmare, but they also reasoned that this was their moment to finally own a home in Australia 2024. Local real estate agents were only too happy to facilitate.

Having helped write the first draft of history, a year later, I would be in town in the lead up to the one-year anniversary. What I found was a community still reeling from the disaster, a far cry from the glossy press releases about how it was all going strong. People had died during the disaster, and many had lost everything. Those who remained were grappling with all the usual problems concerning insurance and recovery. The state government had tried to set up a buy-back program that allowed people to retreat from areas prone to catastrophic flooding, but the process was haphazard, uneven, poorly administered and at times confusing for people with low acumen who were largely left to wrangle paperwork the best they can. Many simply gave up.

What can be learned from these two contrasting stories? For a start, there are two contradictory ideas when we talk about the impact of climate change and class. On the one hand, we have an idea that: “rich or poor, climate change affects us all”. On the other: “those worst off hurt the most, first”. Often these are framed in ways to make class seem irrelevant to discussions about climate. It may be true, for instance, that a bushfire doesn’t care about the size of your bank account, and that plenty of rich people live in climate-exposed locations. Likewise it is always true that there’s always someone worse off than you. Zoom out far enough and there are any number of communities in developing countries already struggling to sustain themselves. Residents of Tuvalu are watching the ocean swallow their home; at one point nearly a tenth of Pakistan was underwater in another, separate catastrophic flood.

These are both true statements, but they are details that do not exist in isolation. Whether you’re thinking about climate change and class on a global, or national scale, the basic dynamics do not change. It is also true, for instance, that when the chips are down, rich people, on balance, can move — and can move early. It’s much harder to leave ahead of the storm if you don’t own a car in a region with no mass transit. It is similarly true that poor, working and even lower-middle class people have fewer choices about where they can live and the dynamics of an increasingly unequal society tends to funnel them into higher risk areas. This it true whether someone makes their home in the shadow of Warragamba dam, on the baking or the drought-prone Adelaide plains. It is also a reality that the people who fall into these categories are often migrants, the children of migrants and Indigenous, meaning that they will confront a raft of problems ranging form employment discrimination to police violence. Throw into the mix the reality of debt and unstable income in an increasingly financialised society, and those with fewer means will struggle to cover their debts if something goes wrong. When it comes time to absorb a shock, the people with money win out every single time.

Another true statement is that the Australian political system, circa 2024, is not generally geared to respond to the material concerns of poor and working class people at the best of times, except in moments of great pressure. Sure, a sympathetic government may knock a few dollars off the price of medicines, but raising social security to the poverty line or investing in basic services at the level needed to counteract the austerity of the last few decades? Forget about it. Moreover the responses sought by these communities are more likely to require collective action through institutions with a shared pool of resources — like government. Despite pretty words to the country, this is something Australian institutions have long since abandoned in favour of solutions that promote “access” and offer “clever” fixes to “wicked” problems.

Since the flood, for instance, the residents of Lismore have organised to assert some agency over how their city gets rebuilt. This sort of thing takes money, however, and these efforts hinge on public funding, a capable bureaucracy and a responsive political leadership that can maintain focus long into the future. Marshalling these resources is hard work. Compare this to the residents of Collaroy who largely self-funded their preferred response to an increasingly volatile climate system. There’s was a preference that privileged their needs over the risk to public good, but required nothing more from the local authorities than a nod to go ahead. No one had to think too hard about plans for “managed retreat” — words to strike terror into an Australian politician conditioned to project “strength” to the electorate at all times, and at all costs. To do otherwise would be too hard; it might require something that looked like work.

Good Reads

Because we here at Raising Hell know how much you love homework…

There have been more than a few hot takes on Trump: The Sequel, but Ben Davis writing in The Guardian US edition makes a convincing case that it has a bunch to do with offering people a safety net, and then snatching it away again.

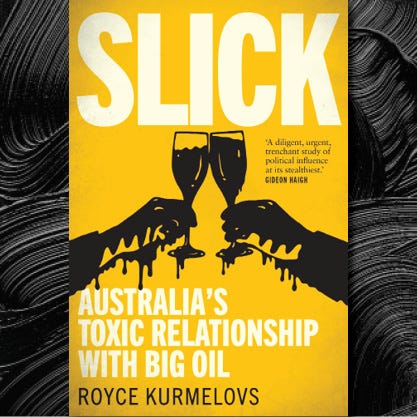

"Many books about climate change are worthy but dull. Slick, however, is as readable as it is shocking." - Richard Denniss, The Australia Institute, writing in The Conversation.

Reporting In

Where I recap what I’ve been doing this last fortnight so you know I’m not just using your money to stimulate the local economy …

‘Flexible EV charging stations prove to be good for solar soak, and it stopped ICEing’ (The Driven, 8 November 2024).

‘Santos faces greenwash charge’ (The Saturday Paper, 9 November 2024).

‘The Australians who sounded the climate alarm 55 years ago: “I’m surprised others didn’t take it as serious’” (The Guardian AU, 10 November 2024).

I’ve also been a contributed on four other stories, totally around 10k words that I am waiting to go live — so you might say it’s been a busy couple of weeks.

In the meantime, however, I have some news, Slick has made the shortlist for The Walkey book award.

Before You Go (Go)…

Are you a public sector bureaucrat whose tyrannical boss is behaving badly? Have you recently come into possession of documents showing some rich guy is trying to move their ill-gotten-gains to Curacao? Did you take a low-paying job with an evil corporation registered in Delaware that is burying toxic waste under playgrounds? If your conscience is keeping you up at night, or you’d just plain like to see some wrong-doers cast into the sea, we here at Raising Hell can suggest a course of action: leak! You can securely make contact through Signal — contact me first for how. Alternatively you can send us your hard copies to: PO Box 134, Welland SA 5007

And if you’ve come this far, consider supporting me further by picking up one of my books, leaving a review or by just telling a friend about Raising Hell!