Raising Hell: Cracking COVIDSafe: Part 5: In For A Penny

In which we keep our nose to the grindstone...

When the letter came back from the DTA explaining they were going to stick to their guns over the $750 charge, I had two points of interest. First was the description of the search process and documents identified to date:

This would be the first time anyone had actually explained how the search was conducted on my application and what it had turned up. The other was the refusal to waive the fee on public interest grounds:

Though the agency may have still been intent on charging like a bleeding bull, they were kind enough to drop a couple of bucks off the sum, leaving it at $721.93.

On 7 September 2020, another letter from the DTA landed in my inbox, continuing along a similar theme. In short, they had relied on Section 7 of the Freedom of Information Act (1982) — which says they don’t have to release documents originating or sourced from intelligence agencies — to refuse access to one document of those they had identified as being “relevant” to my request.

The rest? Well:

That third party, for what its worth, was the Boston Consulting Group whose confidentiality clause in their agreement would prove something of a sticking point as it was relied upon to refuse applications. Essentially it was a mutually beneficial catch-all secrecy provision. During its scandal at ANU the company pointed to the confidentiality clause as a reason it had to carefully monitor what its employee said at public events out of concern for “client confidentiality”. Government agencies, meanwhile, could shrug off a request by pointing to the clause and saying they didn’t want to sour their relationship with a given company.

But that was fairly hypothetical. In the end the reality was the DTA had handed over just three documents. To lay eyes on them, I would still have to lay down the final $533.65. So I paid up and what I got for my money were a couple of emails and a portion of a technical document that can be found here and read like this:

To sum up, the agency had slugged me $721.93 for a grand total of three documents based on a search I just had to trust was thorough and conclusive. Not only that, but the agency had automatically redacted the names and details of employees under Section 22. That section allowed a decision maker to redact “irrelevant matter” in an application and is often used to automatically blot out the names of public servants — a practice that is generally frowned upon. Part 6.153 of The FOI Guidelines makes clear that names should not be automatically redacted and the practice was also called out in a 2019 discussion paper from the Office of the Information Commissioner.

In response, I drew up a quick response asking for an internal review of the decision. When I checked those sections of The Freedom of Information Act cited to block release, I found the reasons given for their decision were — in my view — shallow. None appeared to take into account the factors favouring release — and so I pointed that out. On top of that I, wanted the names of public servants to be restored and a more detailed explanation of how 23 documents could be identified but only three delivered.

Then I sent it off and waited.

Already, I had several points to make about the whole process. I had questions about the search performed by the agency: Did it capture the material relevant request? Is plugging in certain keywords into a database enough? Did they go broad enough? Did they interpret my requests correctly?

On top of this, there was another issue about deterrence. The high cost of the application on questions of clear public interest — a point acknowledged by the agency in their letters to me — could have been understood, whether real or merely perceived, as a deterrent to going through with the application. That was a problem. When considered against the number of documents released following the agency’s consultations with party’s unknown from BCG — Who exactly were the people? What was said during those consultations? How much weight was given to their input over mine? — it was a pattern that meant, as a reasonable person, I might be justified in thinking someone was taking the piss.

To be clear, I had no issue with the individual FOI officer who actually handled my requests. All communication with the agency were handled through a single point of contact who was always courteous, responded promptly and was uniformly personable. They were also — perhaps by design — not the ones calling the shots.

By this point I had already decided to push the whole thing to external review. That decision was not personal. It is a democratic right within Australia to have an executive decision of a government body checked in this way. Even if I was totally wrong about all of it, applying for a review to the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) offered a way to check the agency’s work and verify that yes, everything had been done correctly. If the OAIC came back and agreed with me, even better. That way, I’d get access to documents, a refund and hopefully another insight.

Other reporters, it should be said, have had a much tougher time with the DTA. While I decided to chase those documents relating to questions of public expenditure, others on the tech beat went after different targets. When ABC’s tech reporter, Ariel Bogle, went after documents that may shed light on how many active users COVIDSafe actually had, she posted to Twitter about her response in a now-deleted post:

The Guardian’s tech reporter, Josh Taylor, would have similar trouble:

What this did is reinforce the perception of all-pervading secrecy around the app. The multi-million dollar project has found just 17 additional cases of Covid-19 — a point the government has been at pains to spotlight — but the agency was clearly not comfortable answering questions about anything beyond COVIDSafe’s basic mechanics.

For me, this showed the extent to which the project had been a marketing exercise — and a pricey one. In October, the DTA had confirmed before a senate committee that as of 29 September 2020 the total cost to develop and run the app at that point had hit $10 million — not including the cost of advertising. The agency offered these figures while refusing to comment on the effectiveness of the app or offer any other meaningful detail on how it was built.

Of course there was a certain irony to all this given Stuart Robert, the minister who has oversight of the DTA, gave a speech at the National Press Club on 7 July 2020, during which he laid out his vision for a transparent public service:

Going forward, we need to acknowledge community expectations and be transparent about how we manage the information that Australians are concerned about sharing with us. […] This transparency and trust will be critical as we pursue our goal to make all government services available digitally by 2025 and enable our country and people to grow and prosper.

In the spirit of this call to transparency, I saluted the Minister and fired off another round of FOI applications. The first was to ask for documents that may shed light on how the DTA had instructed BCG in development of the app:

the email(s), meeting minutes or briefing documents (whichever is relevant) used by any employee of the DTA to outline or brief the Boston Consulting Group in what was required from the creation and/or development of the COVIDSafe app.

email(s), meeting minutes or briefing documents (whichever is relevant) used by any employee of the DTA to brief Ionize upon commission the penetration test of the COVIDSafe app that was conducted between 24 April to 6 May 2020.

About a week later, I filed a second application asking for:

A list of all Third Parties consulted on [application FOI 199/2020 and;

A copy of any contemporaneous notes, emails or other summaries that may establish what these Third Parties advised the DTA in relation to application 199/2020, particularly anything that helped determine what is "relevant" or "not relevant".

The other lot of applications I sent were to state and federal health agencies to answer other questions I had about how the data collected was actually accessed and used by officials on the ground.

Once this was done, it was only a short wait until the response from the DTA came back on 22 October 2020. The result was predictable. Not only was the agency sticking to their guns, they were going to vary it to make it stricter:

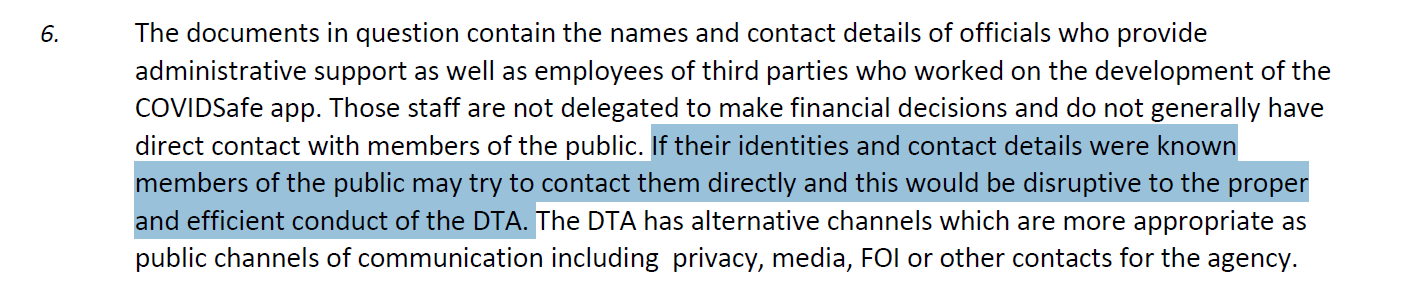

To justify the decision to redact names the decision maker cited Section 47E of the Act that allows an agency to refuse applications where it had a reasonable impact on their administrative functions. In this case, the decision maker had pointed to sub-section (d) — that says an application can be refused where it would have a “substantial adverse effect on the proper and efficient conduct of the operations of an agency”. The reason for this gave me a chuckle.

God forbid a member of the public service or the companies they contract with be sent an email by a member of said public. What a nightmare.

The decision letter went on to say the release of the names would do nothing to “improve the accountability of the DTA as none of the names are of staff with financial delegations or accountability for the production of any programs including COVIDSafe”.

All of which gave me enough material to string together an appeal to the OAIC, but while I worked on that application, I also began to hear back from the health services I had applied to — and that proved revealing in unexpected ways.

Cracking COVIDSafe is a feature series made in association with Electronic Frontiers Australia. It aims to highlight the importance of Freedom of Information as an essential tool for holding government to account while helping to teach people about the process so they can do it themselves.

The journalism published by Raising Hell will always be free and open to the public, but feature series like these are only made possible by the generous subscribers who pay to support my work. Your money goes towards helping me pay my bills and covering the cost of FOI applications, books and other research materials. If you like what you see share, retweet or tell a friend. Every little bit helps.