Raising Hell: Cracking COVIDSafe: Part 6: God Bless South Australia

In which we take advantage of a loophole...

If there’s anything we need to be absolutely clear about it’s this: mistakes happen. They’re a fact of life. You can try your best to make something perfect but when it comes down to it, there’ll always been someone out there in the world who’ll come along and point out the thing you missed. When that happens, you can either get angry at them for being honest, or you can try to fix the problem — though if you can’t even do that, you can at least correct the record.

After the last instalment of CrackingCOVIDSafe went live, it quickly became clear I had missed the story. If my focus had been on the $700 price tag of the documents I obtained, it was soon pointed out to me the documents themselves may be worth more than I realised.

Among them was a copy of a “sprint plan” that described the work to be done on the COVIDSafe app over five days in late April:

When paired with the fact the COVIDSafe app launched on 27 April 2020 this became important for two reasons.

First, in making my FOI application to the DTA, it was now clear the agency had not given me what I had asked for. In applying for documents about the creation of COVIDSafe, I had instead been given documents drawn up after its release.

The other point of interest lay in what they actually said. All along the people who had independently investigated the botched job had said the government spent the first few weeks making cosmetic upgrades to their app and not acting on the security flaws being found. These documents now constituted proof as they showed the work performed on the first update:

The headline wrote itself: the Australian government released software that breached its own privacy policy and did nothing to fix it for weeks after the issue became known. Here was the proof. For a point of comparison, when Singapore — noted democratic utopia — learned about a security issue that made it possible to identify users who were supposed to be anonymous on April 30, they fixed it within six hours. Australia, on the other hand, took weeks. This meant a place once described as “Disneyland with the death penalty” was more open and responsive to engagement with the public than the Australian government.

The lesson here is one about handling paper sources. There is a process. When you get them, read them. Then read them again. Then go ask someone who knows what the hell they’re talking about for good measure.

How To Find A Loophole

From the start of this whole project I had two specific questions I wanted to follow up:

How well had federal government efforts to protect people’s privacy through legislation actually worked? and;

How much did the COVIDSafe developers actually know about BlueTooth technology?

What I did not anticipate is how the answers to these questions would be found in the instructions health officials had been given about how to actually get hold of the data COVIDSafe was ostensibly collecting.

As far as division of labour went, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) had been responsible for teaching medicos on the ground about how to actually get hold of the information collected by COVIDSafe. To get hold of these documents, I ended up filing three FOI applications to the health services of Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia asking for this material. I would have done this for every state and territory but at roughly $30 a pop, I didn’t have enough sweet Substack money coming in to cover another $560 expense.

In September, after several delays and a couple of months, I began to hear back. First out of the gate was Victoria. The state that had just endured a months-long lockdown refused access outright, citing Section 29 of the state’s FOI laws:

It was a similar story on the other application I put in with New South Wales Health. While Victoria and New South Wales both recognised the public interest in the documents, they refused to hand them over on the basis it may anger their federal counterparts.

SA Health, on the other hand, had been dragging its feet for months. Having had rejections from both Victoria and New South Wales I had, out of curiosity, double checked SA’s FOI legislation. I did not find an equivalent process that could be used to block my other applications in Victoria or New South Wales, but given my track record, I didn’t have much hope for success.

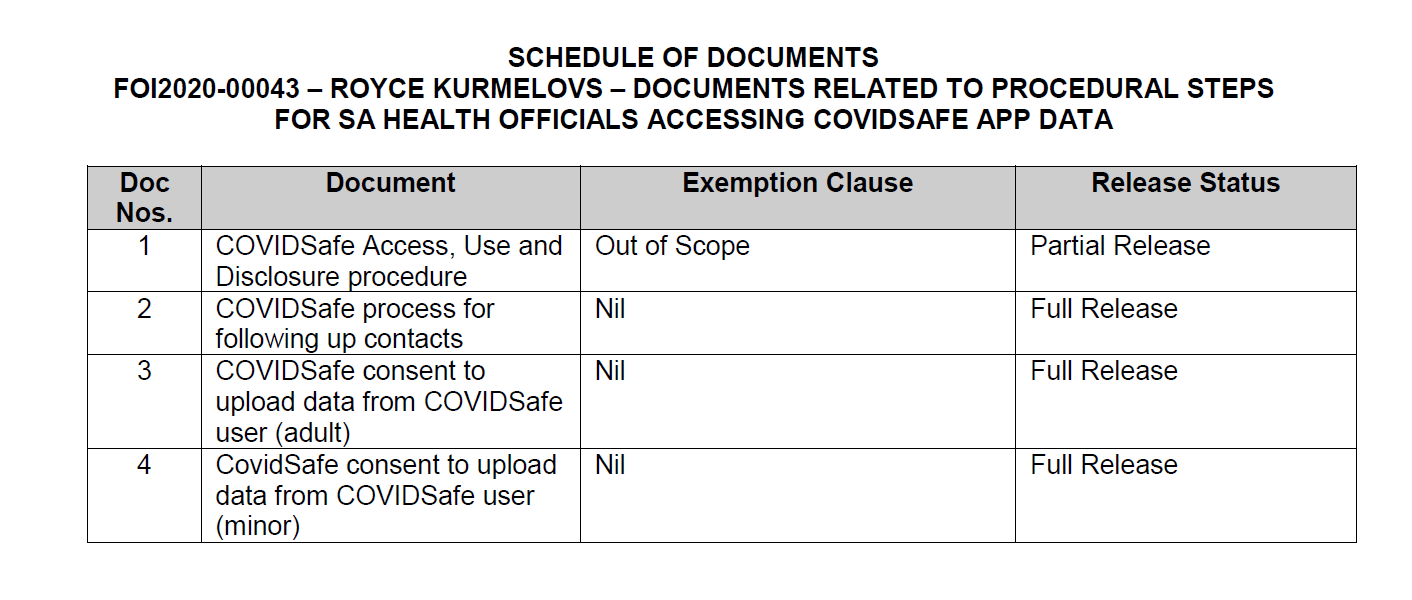

What I did not know was that SA Health were about to come through. After months of silence, I followed up before receiving a phone call from an FOI officer who apologised for the delay and asked if I would be willing to accept a “draft copy” of the instructions I had asked for. While they knew there was a final copy somewhere — they had seen it — they couldn’t actually find the final PDF. I told them that was okay by me and in the dying days of October, I got them back:

There was a valuable lesson in this. If we think about Australia as a metropole with political, commercial and social activity all increasingly concentrated between Sydney and Melbourne, this is reflected in the composition of each state’s FOI Act. That jurisdictions like New South Wales and Victoria even have provisions to “protect” their relationship with the federal government — and that South Australia does not appear to — tells you something about the arrangement of political and economic forces in this country. More importantly, this exact dynamic can sometimes become an advantage, especially when looking at a national program like COVIDSafe. Putting in an application out in the periphery is one way to get answers about a federal program that operates nationally.

The Docs

As the documents contained links or contact information for contact tracing teams that probably should not be easily accessible or searchable on the internet, I have manually redacted and re-scanned them into PDF. They can be read here.

On my first read through, the biggest takeaway for me was just how silly the federal government’s attempts to keep them secret actually were. What they showed was a fairly strict privacy regime that governed the acquisition, sharing and destruction of data obtained by COVIDSafe.

At page 10 under “Records Management” the guide broke down the process for accessing and using the data obtained during the contact tracing process across a multiple-page table. Each step clearly showed which jurisdiction had authority over what information was created at every point in the process. The critical bit, however, was the point where federal information was “transformed” into state data and so governed by state law:

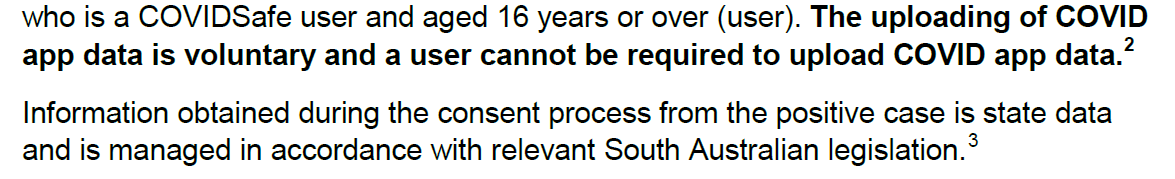

From a privacy perspective, this was interesting. The right to privacy is not absolute, particularly during a global pandemic that has killed 1.48 million people worldwide and will kill more by the time this hits inboxes. To handle that situation means someone’s privacy will inevitably be violated in order to protect everyone’s safety.

That being said, it does raises a question about whether this information is secure — a question I asked in my very first story about the app. When I spoke to lawyer David Watts he described the plumbing by which data gets shared between states and territories.

“You need to look at it from end to end. So, when from where the information first goes into the app and when it comes out the other end and goes to state and territories,” Watts said. “Unless you do a privacy assessment that goes to all states and territories — and I don’t think the Commonwealth has done that — you can’t do a privacy assessment.”

Thanks to a web of interlocking laws that forms the information-sharing regimes between jurisdictions, what a person tells the Department of Housing may end up with the Australian Federal Police in minutes. To make people feel better about using the app, the federal government tried to address this by expressly banning the use of the information it collected anywhere but the contact tracing process.

According to a follow up analysis by David Watts it was, under the circumstances, a pretty good effort. The challenge for the government was that they were attempting do something akin to putting toothpaste back in the tube. After decades of near-total indifference to how the average person’s data was hoovered up by a vast constellation of private companies, law enforcement and intelligence agencies, they were now trying to put a hard limit on how certain information could be used by those organisations. The sheer complexity of the legal structures they were dealing with made it almost impossible to guarantee something wouldn’t end up where it shouldn’t given the potential for quirks, exceptions or errors in state law.

And as it turns out, data from the app was turning up in databases held by the country’s intelligence agencies. When the Inspector General of Intelligence and Security looked closely at they issue in a report published 23 November 2020, they found unspecified Australian intelligence agencies had “incidentally” been collecting COVIDSafe data. How this had happened or which agencies held the information was not made clear. The report simply said the nation’s spies were taking immediate steps to delete the data and promised they had not decrypted the information.

If the privacy issue was one thing, the other point of interest were the scripts written for contact tracers when speaking to someone who is a confirmed case. Most were pretty straight forward and harmless, but what made them interesting is what they didn’t say. At no point do they direct a contact tracer to tell a person how any information they hand over would be treated with the strictest confidentiality and could not be used to prosecute them. As events during the recent outbreak in South Australian show, this is important.

The good news for anyone who may be worried is that the documents make extremely clear — repeatedly — that the decision to upload data collected by the COVIDSafe app is voluntary:

The other point of interest was what it revealed about the depth of the developers understanding of BlueTooth technology:

Though it had been italicised, the word “may” was easy to miss. It was a minute detail in a technical summary that most would skip over without a second thought. When I followed up with Jim Mussared it was the first thing he pointed out.

“I wish I knew what they meant by ‘may’,” Mussared said. “Signal strength decreasing with the square of the distance is an unavoidable consequence of living in a three-dimensional universe.”

BlueTooth signals, for the record, absolutely do lose strength over distance. They are also absorbed or blocked by objects. This is how a microwave oven re-heats lasagna. How the DTA had arrived at a position of doubt about this remains unclear — though there was no way to be sure. The appendix mentioned in the document had not been included, either because it was a draft, or it wasn’t considered relevant.

The next item of interest would be found not in the documents obtained from SA Health, but in the response that came back from the federal Department of Health. In refusing my request to get access to roughly the same documents I already had, they relied on Section 47E(d) of the Freedom Of Information Act. The gist of their argument was that releasing the documents would have a “substantial adverse effect” on the department’s internal administration.

The specific reason cited?

Training.

More or less the department’s big fear was that giving me the material would somehow undermine the training of health officials.

“Disclosure could also affect the department’s ability to engage with third parties for the delivery of training material in connection with the COVIDSafe app,” the decision said.

Now this gave me a laugh. Apparently handing out material that was handed out in training session anyway would somehow make it harder to conduct said training in an unspecified way.

By this point I almost couldn’t be bothered fighting over it, but then I am both stubborn and curious. The refusal was so sloppy, I couldn’t help myself and drafted a short request for an internal review pointing out the obvious: that informing the public about what occurs during the process of contact tracing would make people more likely to cooperate as they understood what was going on. What I didn’t anticipate is how the same morning I sent that request back to the department, the government appeared to be changing tack on COVIDSafe.

Post Script

After months of insisting nothing was wrong, and mere weeks after Stuart Robert, the minister responsible for the DTA, had been promoting COVIDSafe as “one of the finest tracing apps on the market”, the government announced a revamp. Rather than admit the whole exercise had been a rushed and costly boondoggle that had enriched a clutch of private companies at the expense of the public interest, Robert was busy bailing water by trying to retrofit the app using software called “Herald”.

The details of Herald are boring and complicated, but the fun bit is what happened after the DTA uploaded the source code for their proposed refit onto the internet with no supporting documentation or information. Almost immediately a farcical skirmish broke out in the media and on the internet as the open source community, surprised by the announcement, began to look at it closely.

On one side of this exchange were the grey, anonymous bureaucrats of the DTA and the staff of Minister Stuart Robert who genuinely seem to think they had done a good thing. On the other were the rowdy, quasi-anonymous denizens of the internet who were long past accepting platitudes and talking points.

Within 24 hours, tests performed by the open source community showed how the app chews threw the phones battery life and requires constant access to a person’s GPS to work. If there was a known problem with getting iPhones to talk to each other properly with the app, Herald tried to solve it by setting up a relay system that simply did not work. There were also security issues. Better yet, people immediately pointed out that the British government, back when it was designing its own contact tracing app, had abandoned Herald when it became clear it was clunky and unusable.

As soon as the media began reporting that Australia was now recycling software the Brits had rejected, the DTA tried to correct the record in a series of posts to its official Twitter account. The agency went to great effort to explain how Herald was actually open source and free software, meaning they could fix COVIDSafe at no additional cost to the public. In doing so, however, the agency omitted how the company that wrote Herald was also the same company that initially worked on the British government’s original, now-abandoned contract tracing app — a fact quickly pointed out in response to the agency’s post. Then when The Guardian’s tech reporter Josh Taylor called to clarify the exact point Robert’s ministerial advisors had actually been trying to make, the advisors reportedly ranted on the phone about the Google-Apple contact tracing app.

Now, all of this could have been avoided. Had the various branches of the Australian government not been so cagey about actually talking directly to members of the public, it is possible a dialogue may have been established before any decisions had been made — saving them from embarrassment.

Then again, the priority from the get-go was never about delivering Swedish-quality public services, but about protecting the reputation of the agency — and the minister who heads it.

Cracking COVIDSafe is a feature series made in association with Electronic Frontiers Australia. It aims to highlight the importance of Freedom of Information as an essential tool for holding government to account while helping to teach people about the process so they can do it themselves.

The journalism published by Raising Hell will always be free and open to the public, but feature series like these are only made possible by the generous subscribers who pay to support my work. Your money goes towards helping me pay my bills and covering the cost of FOI applications, books and other research materials. If you like what you see share, retweet or tell a friend. Every little bit helps.